Rural Utopias Residency: Tina Stefanou in Carnamah #3

Tina Stefanou is currently working with the community of Carnamah. This residency forms part of one of Spaced’s current programs, Rural Utopias.

Tina Stefanou is an Australian-Greek artist based on Wurundjeri country in Wattle Glen, Victoria. With a background as a vocalist, she works undisciplined, with and across a diverse range of mediums, practices, approaches and labours: an embodied practice that she calls voice in the expanded field. Informed by diasporic experiences, Stefanou engages in sound as social practice and explores with and beyond the all-too-human and more-than-human voice.

Here, Tina shares another update from Carnamah.

Out here on Amangu Country between Carnamah and Three Springs, rare wildflowers grow on the side of the road. They bloom for two months of the year uncultivated by human or machine. These interstitial miracles endure alongside the logistics of post-Fordist crops. A “planetarity” shoots through the not-so-local dimensions of annual harvest and seeding. I am now two weeks into my five-week stint and the land is full of colonial habitations as is the nature of capitalist agriculture. Carnamah is a predominately Anglo-settler farming town, where I have met only one Indigenous person. There is also the presence of Southeast Asian immigrants moving into the region. The family that works at the local IGA have moved from Footscray in Naarm to build a new life here.

Lou Cole, my local guide and producer, took me to a farm that has implemented non-chemical fertiliser and spray. The crops were full but not as big as the chemically induced ones. The magic is in the nuances, the sandy earth, the two-hour travelled sea breeze, the ant hills, the funny shrubs with big noses and groovy haircuts, and the millions of different flower species unique to this region. Lou says that she doesn’t think there is much out here to show, as it’s dominated by the monocrops, but together we see-feel the smaller multiplicities.

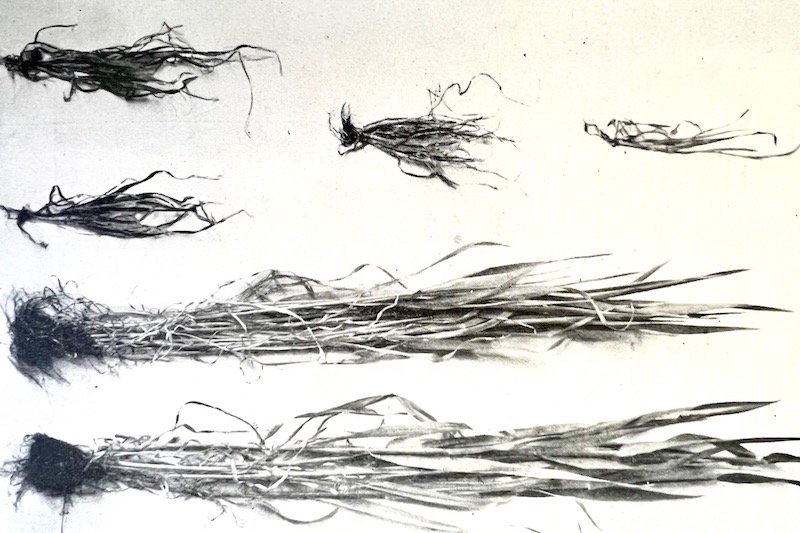

Michael Taussig’s words keep me company during long quiet days. With only 300-400 people in the area, no car and not many public events or spaces, endless fields turn into endless notes. He says: "…for God’s sake, keep your eyes open, notice what is going on around you?"[1] I didn't bring paints for painting, or much electronic gear to capture (aside from my phone). My time is spent in relation to walking, drawing, writing, vocalising, and listening - time spent in experience rather than producing. A part of me feels lazy for not throwing myself into the art space with found objects, soil, historical artifacts, and a smock. It is unclear as to how practice will evolve here. The expectation of cultural production is jarring, how does an artist enter a space that is unknown and full of extractive practices? I do not want to position the role of the artist as an amplifier or facilitator.

Today we visited the place where giant machines get fixed and sold, another space of everyday agricultural mundanities. For me it was a site of new skills and possibilities. I was taken by the largeness of these dinosaurs and the way in which they are imported from the United States to this land. Such heavy maritime movements. Three machine literate men sing along to the radio whilst tucked away under the belly of the beasts, humming along to Nicki Minaj rhymes. Sweaty butt cracks, a bottle of beer and a few missing teeth catch my eyes.

I am invited to step into one of the harvesters, a very teethy animal. Luxurious and full of high-tech computers, I feel as if I am in a VIP cinema. These computers scan the crops and map out where to go, a huge leap from the original plough. Two-way radios still play an important function in these machines, the signal stretching out to 160 kilometres. Airwaves for large bodies to communicate with other large bodies about traffic and hazards. My body feels small in relation to all this, like a drawn stick figure in a hyper real simulation environment.

“We are so far away from our spaghetti,” I say to one of the mechanics. Most of us have no idea as what types of resources, lives and labours are moved for our easy access to food, at least in the middle-class cityscape. There is nothing easy about finding a way in, a slip stream, as Mattie Sempert would say - the Agripoet(h)ics are slow, complex, and hidden in the plain sight of grain. Like searching for rare wildflowers on the side of the road.

We head to a large nature reserve, its dense, noisy, and chaotic, the opposite to the ordered geometry of crops. Divided by sandy rock earth, you get the juxtaposed silence of the money field. One part is allowed to flourish in its ordered chaos and the other part cultivated in the image of Christ. Wheat is the glue, an interstitial murmur in our lives. The rise and fall of empires rest on these crops. Marriage, domestication, family, capital all co-evolved with the spreading of grain. Of course, we know this in a sleepy way, like we know that cattle are the root word for capital, language and materials unconsciously filling our bellies. To explore the logistical and everyday pragmatics of grain cultivation takes the romance out of the grain and shrinks the distance between food production and the consumer. The romantic grain is the romance of labour: fields of gold, spring harvest, songs, sunsets, and fertility. With immanent food scarcity and sovereignty happening all over the globe, what’s on the menu here is chemical fertilisers, large machines, corporate owned lands, ongoing colonisation, emerging diseases from environmental factors and precarious income streams for local family farmers and labourers. Beyond the re-telling of capitalist tales what is an artist to do?

The wind speaks; a cyclone tore through these parts just eighteen months ago with many homes, businesses and locations still being repaired, with many still to receive emergency funds from the state government. I visit a suburb in Three Springs, mainly fibro homes that range from $40,000- $110,000. Lou lives here and we talk about the precarity of living in fibro homes during times of environmental disasters. Mould, leaks, sunken floors, lack of insulation are key features to these matchstick shelters. But we love them, there is a feeling of eternal childhood sleep overs. How will local and national governments make sure that the homes of the rural working-class won’t melt into the hot earth?

[1] Michael Taussig, I Swear I Saw This, Drawings in Fieldwork Notebooks, namely my Own, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011) 50.

Images courtesy of the artist.