Rural Utopias Residency: Alana Hunt in Kununurra #4

Alana Hunt is currently working with the community of Kununurra. This residency forms part of one of Spaced’s current programs, Rural Utopias.

Alana Hunt is an artist and writer who lives on Miriwoong country in the north-west of Australia. This and her long-standing relationship with South Asia—and with Kashmir in particular—shapes her engagement with the violence that results from the fragility of nations and the aspirations and failures of colonial dreams.

Here, Alana shares an update from Kununurra.

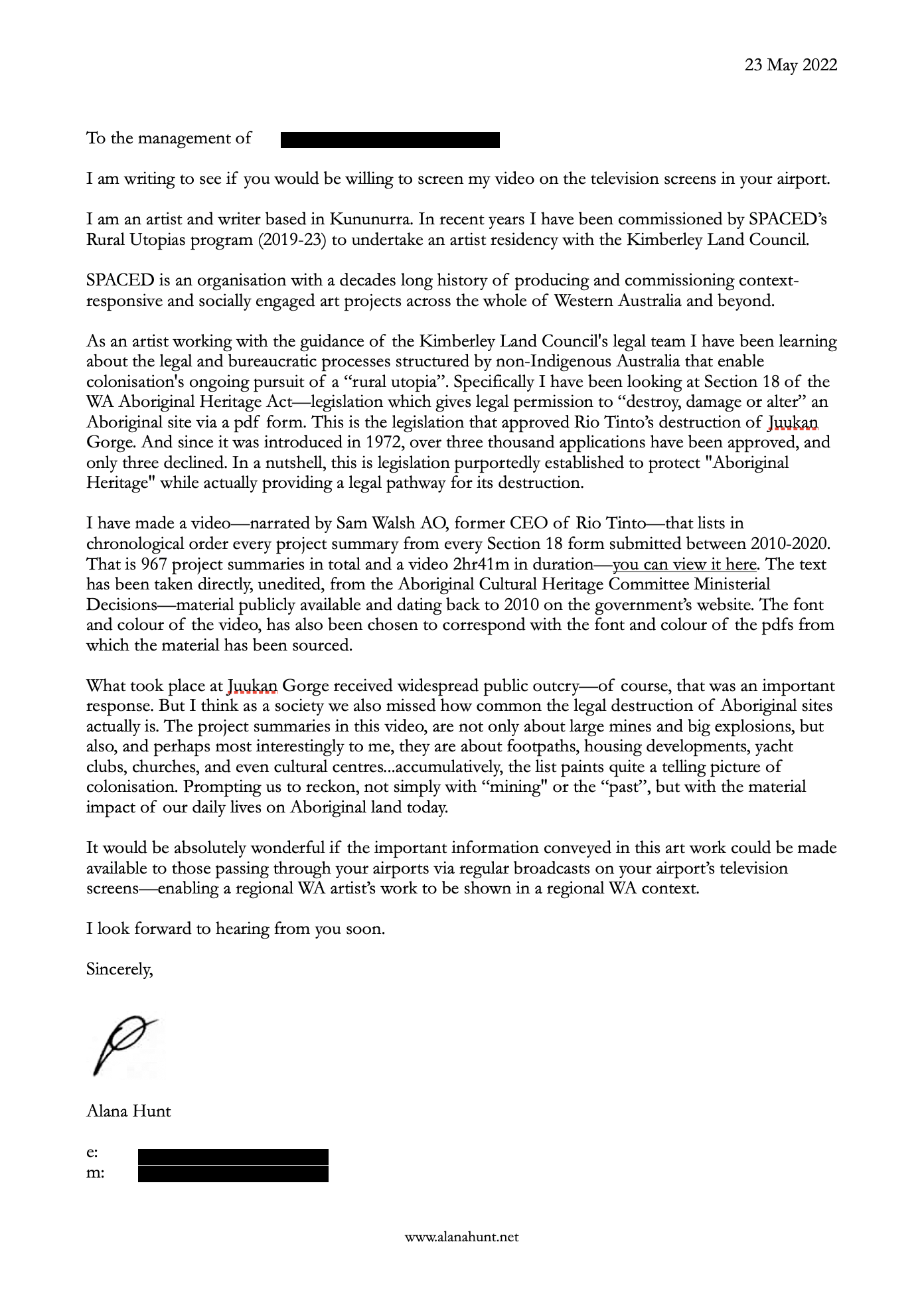

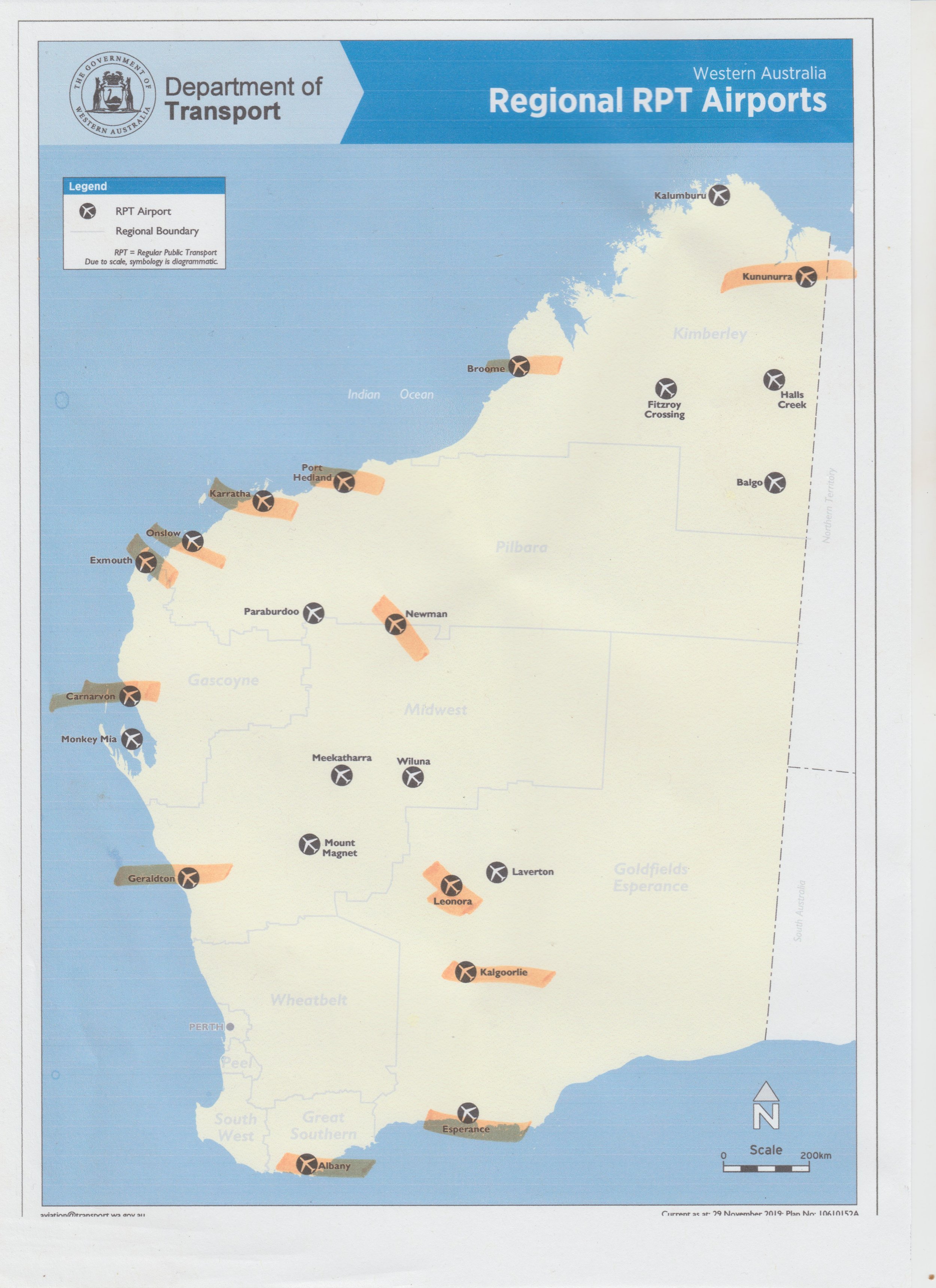

Phase Two of my Rural Utopias residency with SPACED and the Kimberley Land Council commenced in May 2022 with a letter, addressed to (what I hope is) every airport in regional WA with a television screen. I asked if they would be willing to screen my video on Section 18 of the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act that Sam Walsh AO has narrated, and which I have subsequently titled, Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven.

One of the thirteen airports responded almost immediately—instilling a sense of hope and possibility:

Hi Alana,

All of the airports advertising spaces are managed by an external company called XXXXXXX XXXXX. You can contact then on XXXXXX XXXX.

Kind regards,

I replied with equal swiftness, hoping to keep the ball rolling:

Thanks for your prompt response.

Rather than advertising spaces, I am more interested in screening my video on one of the television screens—that would normally show the news at your airport.

Who is in charge of what is played on the television sets?

Warmest thanks,

Alana

No reply.

Of the thirteen airports I wrote to only two replied—despite numerous follow ups. The silence of my own shire was the loudest. But the reply I received from an airport in the south of the state showed some consideration and thoughtfulness:

Screening as proposed is unfortunately not something we’d be able to approve, as private use of the TV screens isn’t within the scope of our Management Practice for XXXXXXXXX Airport Advertising Opportunities so it’s not a service on offer to any other party.

That said, I think there may be potential that we could promote the material elsewhere within the Shire of XXXXXXXXX, so I’ve asked XXXXX XXXXX from the Shire’s Reconciliation Action Plan Working Group to read your proposal and she should be in touch with you in the coming week.

Have a lovely afternoon!

Ultimately this Shire’s Reconciliation Action Plan Working Group didn’t find a home for my video. And that’s fine. But the email exchange did bring to mind Tess Lea’s book Wild Policy: Indigeneity and the Unruly Logics of Intervention (Stanford University Press, 2020). And here, I would like to share three excerpts from Tess Lea’s final chapter from this book—Wild Policy Manifesto, specifically Step 3: Care for the micro:

I have been at pains to point to the pains people go to, the pains people experience, in making policy “work”. Within policy ecologies, the opportunity to make little differences sits with everyone all the time across a distributed field. It is always an option for street level bureaucrats to turn a blind eye, to help translate forms, to bend a rule. Whether someone is favoured and argued for, dealt with caringly or with cavalier indifference—all are transacted within these domains of the micropolitical, domains that are never so miniature or isolated once we admit their greater significance. (p.162)

…

This remains a key insight: microlevel attention and care matter greatly to how policy is enacted and experienced in the everyday. There is a lot that can be done within these interactions: and even while emphasising issues of unsustainability, stress, toll, and turnover, I have tried to honour the fundamental importance of daily acts of courtesy and ethical expertise. Microlevel care is not restricted to service transactions but can include carpet worlds. The people involved in artifactual policy formulation within policy citadels operate as brokers and translators too. When they nudge wording to limit damage despite being under draconian instructions they are intervening in their zone of influence. (p.163)

…

Simply, being a sensitive and indefatigable policy broker armed with ethical principles and a caring heart is essential, but radically insufficient, to sustain the kinds of interventions that might shift disadvantage out of its well-grooved predestinations. Here the concept of institutional killjoys, adapted from Sara Ahmed’s notion of feminist killjoys, remains highly relevant. Killjoys insist on holding policy to account. (p.164)

…

If forms of administrative violence are embedded within software algorithms and archives, if inequalities reproduce themselves through such ordinary and seemingly unavoidable events as rampant professional turnover and unreturned phone calls, what’s the intervention point for a would-be intervener? Answer: let’s make this less about a labour of individual effort and take advantage of what such an entangled policy wilds might offer. After all, individual efforts are rarely structurally contagious; coalitions, however, are another matter. (p.165)

Tess Lea’s words speak not only to the correspondence (and lack of), that I received from regional airports and their shires in WA. But also, and more importantly, to the implementation and everyday practice of policy and legislation that contemporary Australian society develops. And in many cases it does so, in ways that ensure its own continuation at the expense of its other. This is exemplified in the WA Aboriginal Heritage Act which avows to protect Aboriginal Heritage but in practice provides a legal pathway for its destruction—so long as this destruction is in the ‘public interest’. But there needs to be a challenge to this, a redefinition of what public and whose interest.

Alas, my 2hr41m video produced in powerpoint from the data of state government pdfs was not destined (yet) for the tv screens in regional WA airports. However, soon enough I received an email from the KLC. They were planning a NAIDOC event—a Kimberley Culture and Heritage Showcase of films, dance and talks—aligned with the 2022 theme Get Up! Stand up! Show up! And they wanted to screen my video.

On the evening of 30 June 2022 Nine Hundred and Sixty Seven was projected on the walls of the tin sheds at Goolarri Media in Broome. Sam Walsh’s voice boomed into the open air creating a little sense of confusion, that I hope also morphed into some degree of retrospection.

This was the first time the work had been shown publicly—a world premier, of sorts. About ten months earlier I’d spoken to the KLC about the idea of screening this video in Kununurra and inviting the Miriwoong Wangga dancers to perform ‘in relation and response’ to the video. I had spoken with Chris Griffiths’ who leads the Wangga dancers about this. On one hand the video contains something quite violent, and also sad: mountains of grief wrapped up in the destruction and damage of so very many sites right across WA—decisions made on paper that wreak havoc in the world. But there is also an element of resistance and defiance that could be present in a performative response to the video—in talking back, singing over the audio of Sam’s narration, drowning out his voice and this list with your own song and your own dance on your own Country.

I like to think of time as a collaborator—as something to trust, not fight against. I’d envisioned screening the video in Kununurra much earlier, but many things got in the way. However, its eventual realisation in Broome turned into something quite special—as I put my trust in collaboration with a community over 1000kms from where I live.

Instead of Wangga on Miriwoong Country, on Yawuru Country in Broome the KLC had invited Neil McKenzie to share story and song and dance in addition to the local youth dance group Burrb Waggaraju Nurlu led by Tara Gower. While technical limitations meant we needed to cut Sam’s narration so Burrb Waggaraju Nurlu’s songs could be played—there was something inherently emotional seeing young Indigenous performers obscuring the projection as statements rolled over the wall behind them:

Installation of a floating jetty to replace the existing pylon jetty.

Exploration drilling.

Contamination Investigation and Passive Park and Recreation Development.

Mining.

…to name just four from 967 project summaries seeking permission to destroy, damage or alter an Aboriginal site in WA which Sam Walsh reads aloud for over 2hr41m.

These performances were followed by the screening of films about the KLC’s origins and current work, and words from Tyrone Garstone, CEO of the KLC, about history and work and action and the future.

I remain very thankful that the KLC, an organisation with such a vital role for all Aboriginal people right across the Kimberley, saw some degree of value in this unusual piece of “art” pulled together by a non-Indigenous person who has been burrowing into decades of government reports and threading the contents together in unconventional ways.

It is important that my “art” moves gently in these collaborative and grounded spaces where so-called “contemporary” or “conceptually” driven work often doesn’t venture.

Next stop, Kununurra Picture Gardens!

Images 1 & 2: Letter and map provided courtesy of the artist.

Images 3 - 9: Kimberley Culture and Heritage Showcase, 30 June 2022, Goolarri Media, Broome. Courtesy Kimberley Land Council.